How did the US Constitution Come About and Why Did it Succeed?

After the failed national response to Shays Rebellion, members of the unicameral congress realized that the Articles of Confederation needed to be amended. The Constitutional Convention was a gathering of delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies (except Rhode Island) in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. The delegates were there to discuss the problems with the Articles of Confederation, a document that established the first formal government for the United States after the Revolutionary War. Instead of correcting the issues with the Articles, the delegates wrote a new Constitution, which was ratified by the states in 1788.

Junius Brutus Stearns, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, CC-NC

The U.S. Constitution was written in 116 days at the Constitutional Convention, in Philadelphia, in the summer of 1787. Its purpose was to replace the Articles of Confederation with a better government to meet the growing nation’s needs.

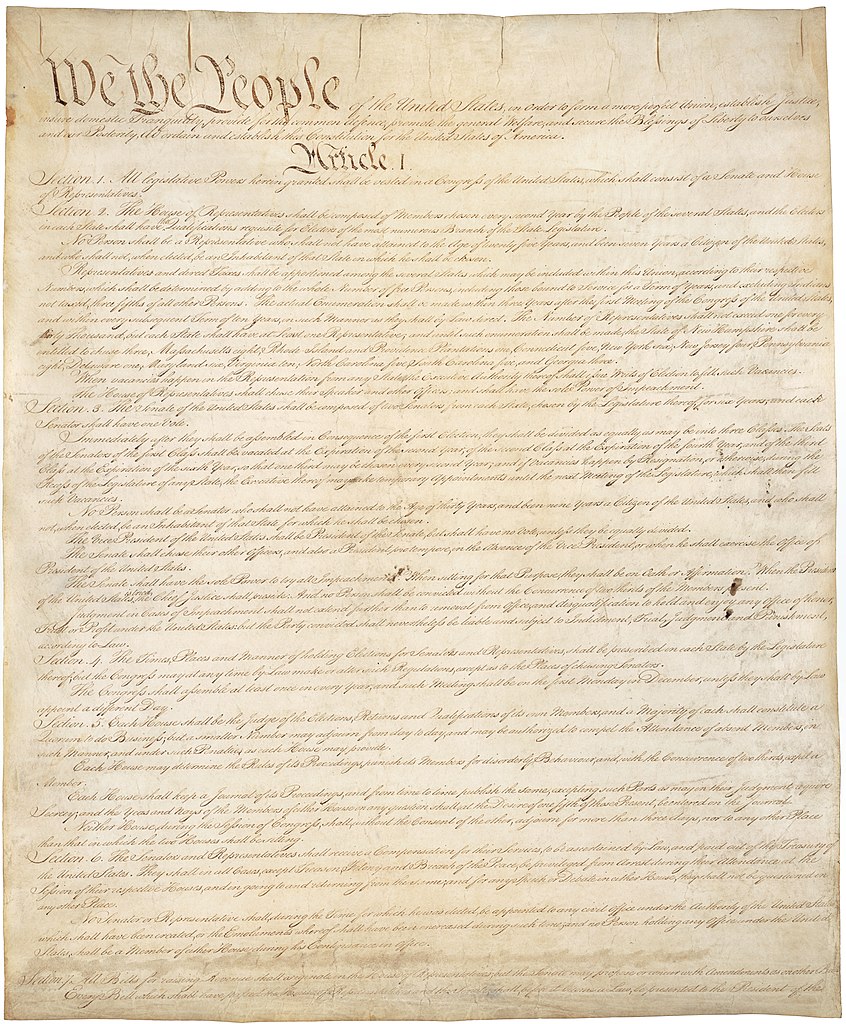

National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Broken into seven articles, the Constitution defines the form and function of the American government. Its first three articles embody the doctrine of the separation of powers, whereby the federal government is divided into three branches: the legislative, consisting of the bicameral Congress; the executive, consisting of the president; and the judicial, consisting of the Supreme Court and other federal courts. Articles Four, Five, and Six describe concepts of federalism—that is, the rights and responsibilities of state governments and the states in relationship to the federal government. Article Seven establishes the procedure used by the thirteen states to ratify the Constitution.

Article I – The Legislative Branch

Article I Establishes the legislature as a bicameral body consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The House of Representatives

Representation in the House of Representatives is based on a state’s total population. The more people who live in the state, the more representatives the state has in the House. The entire House stands for election every two years, making it the federal office closest to the people’s will because the representatives are elected so often. As a result, all bills that address spending and taxes must begin in the House of Representatives.

Today there are a total of 435 voting members of the House. Six non-voting members represent Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Virgin Islands.

The speaker of the House leads the House. Members of the House select the speaker. It is not a requirement, but the speaker has always been a member of the House.

The House has three special powers. First, since House members come closest to the people’s will, all bills concerning taxes or federal budgets must begin in the House. This gives the House the power of the purse because it controls how money is spent in the federal government.

Second, the House has the power to impeach (for charges of “high crimes and misdemeanors”) federal officers, such as the president, members of the cabinet, and Supreme Court justices. Impeachment alone does not remove an elected official from office, but it requires that he/she stand trial in the Senate, where, if convicted, removal from office is possible.

Finally, in the event of an electoral tie or no one candidate earning enough electoral votes to outright win the presidency, the House has the power to select the President. Each state delegation receives one vote, and the candidate with the most votes wins.

The Senate

The Senate was established to provide equality between the states because each state, regardless of population, has two senators. Currently, there are 100 Senators, two for each of the 50 states. Senators are elected to six-year terms. Because of its smaller numbers, the Senate allows for more prolonged debates resulting in a slower-moving legislative body.

The vice president of the United States, called the president of the Senate, is the official leader of the Senate, though the role is much more limited than the speaker of the House. The majority leader leads the day-to-day operation of the Senate. The majority leader is a member of the political party with the most members and is elected to this post by a Senate vote. The majority leader sets the agenda for the Senate, deciding which bills will be brought to the floor for debate and votes. The U.S. vice president is allowed to vote only if there is a tie.

Like the House, the Senate has special powers. It has the ability to ratify treaties, confirm appointments made by the president, and oversee trials of any government officials impeached by the House.

In the case of an electoral tie or any presidential candidate unable to reach 270 electoral votes, the Senate selects the vice president, with each state delegation receiving one vote.

The main job of the U.S. legislature is to write and pass bills that will run the government and improve the lives of its citizenry. For a bill to be approved, it must endure rigorous reviews and votes in both the House and the Senate. Each chamber will often pass a different version of the bill that needs to be negotiated and revised to create a new unified version. This new version will need to pass both chambers again. Once this process is complete, it goes to the president, who can sign the bill and make it a law, veto the bill, sending it back to Congress for a potential Veto Override Vote.

Election day for all federal elects is the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

Article II – The Executive Branch

Article II establishes the executive branch led by the president of the United States. The executive branch comprises the vice president, cabinet, and other executive departments. Its job is to oversee and maintain government functions while carrying out laws passed by Congress.

The president is elected to a four-year term. The 22nd Amendment, ratified in 1951, limited the president to two terms in office. Before this amendment, there was no limit on presidential terms. The president is not elected through a national election; the Constitution created the Electoral College to elect the president. Each state decides how its electoral votes are allocated. In most cases, the candidate who gains the most votes in a state wins all that state’s electoral votes.

The number of electoral votes each state can cast is determined by the number of representatives the state has, plus its two senators. Each state has at least three electoral votes, while states with a larger population have many more—for example, California has 54 electoral votes.

To be elected president, a candidate must win more than half of the country’s electoral votes. There are 538 electoral votes, so the winner must receive at least 270 electoral votes.

The U.S. president does not have the power of a monarch. The power of the presidency is regulated by the Constitution. But the president does have some special powers. The president appoints members to his or her cabinet and judges to the federal and Supreme courts. Cabinet members can serve until the president who appointed them leaves office (they could be reappointed by a subsequent president, but that rarely happens). Judges, however, can serve for life.

The president can also issue executive orders that carry the power of laws passed by Congress. However, these orders can be repealed or replaced by a new president.

Finally, the president has the power to approve, veto, and execute laws passed by Congress.

The president can also pardon people convicted of federal crimes. This power is typically used to correct perceived miscarriages of justice, such as releasing someone from prison who was given a longer-than-necessary sentence

Article III – The Judicial Branch

Article III establishes the judicial branch. However, it only creates the Supreme Court and allows Congress to establish other courts that might be needed. One of the first acts of the Senate was the Federal Judiciary Act (1789) establishing the Judiciary that we know today. This act included describing the membership of the Supreme Court as one chief justice and the number of associate justices, the federal district courts, and an attorney general for the United States.

Judges appointed to a federal judgeship for district courts or to the United States Supreme Court have lifetime appointments. These lifetime appointments are meant to insulate judges from political pressure and encourage them to issue rulings based only on their interpretation of the law.

The Supreme Court has the final say about the constitutionality of laws and actions taken by the legislative and executive branches. Its decisions are final and cannot be appealed.

Article IV – Relationship between the States and the Federal Government

Article IV outlines the relationship between the states and the federal government—that is, federalism.

Article V – Amending the Constitution

Article V explains how the Constitution can be amended. It requires a two-thirds vote of Congress—currently 281 votes in the House, and 67 in the Senate—and 3/4 approval from a special session of the state legislature or 38 states. This is a high bar for any amendment to meet. That is why there have only been 27 amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Article VI – Supremacy Clause

Article VI makes the Constitution the supreme law of the land. States can have any laws they wish, but laws cannot override federal laws, and in a conflict between state and federal law, federal law prevails.

Article VII – Ratification

States the requirements for the new Constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation.