The Great Chicago Fire: A City in Ashes and Rebirth

By 1871, Chicago was the fastest-growing city in the United States. In 1833, it had been little more than a frontier outpost of 300 people. Less than four decades later, it had swelled to nearly 300,000 residents, making it the hub of the Midwest. Its location on Lake Michigan and its network of railroads made it the nation’s link between eastern industry and western resources.

But rapid growth came with risk. More than two-thirds of the city’s buildings were made of wood, including over 57,000 wooden structures. Sidewalks and even some streets were also wooden planks, while countless chimneys and stovepipes dotted rooftops. Shingled roofs and tarpaper siding created a highly flammable environment. The city had endured 20 major fires in the week before October 8, straining its fire department, which consisted of about 185 firefighters and 17 horse-drawn steam engines far too few for a city of its size.

The summer and fall of 1871 had been exceptionally dry. Chicago received only an inch of rain in July and little more in August and September. By early October, the city was a tinderbox.

The O’Leary Barn and the Start of the Fire

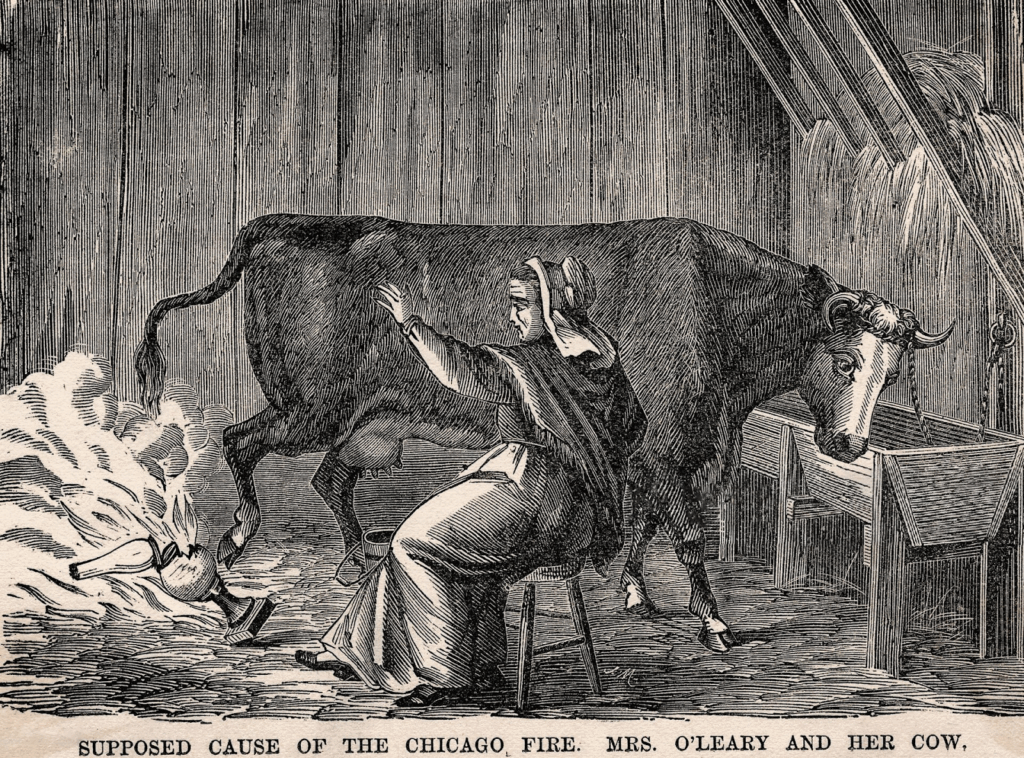

On the evening of Sunday, October 8, 1871, fire broke out in or near a barn belonging to Patrick and Catherine O’Leary at 137 DeKoven Street in the West Side neighborhood. A common legend claimed that Catherine’s cow kicked over a lantern, but Catherine denied it to her death, and the true cause remains uncertain. Some historians suggest it may have been careless smoking, spontaneous combustion of stored hay, or even neighborhood children playing.

What is clear is that within minutes, the flames spread through the barn, igniting nearby sheds and wooden homes. Strong southwesterly winds, gusting over 30 miles per hour, fanned the flames eastward and northward into the densely built residential and industrial areas.

The Firestorm Unleashed

By late Sunday night, the fire department was overwhelmed. Alarm boxes misfired, and some companies were sent to the wrong location, wasting precious time. Exhausted firefighters, already weary from battling a large fire the night before, struggled to control the blaze.

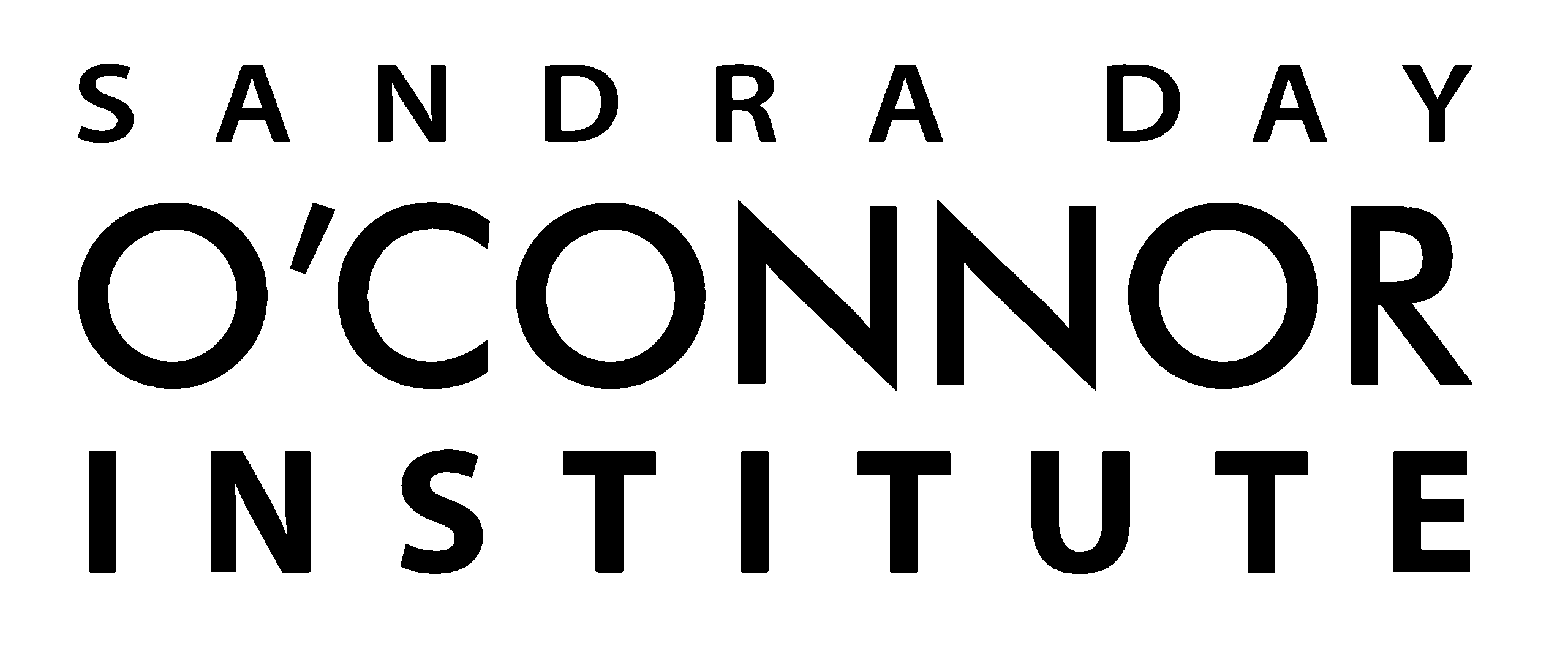

The flames jumped the South Branch of the Chicago River, igniting lumberyards, coal yards, and riverfront warehouses. Burning debris carried by the wind created a “firestorm” that generated its own weather, with temperatures so intense that sidewalks burst into flame. Sparks ignited tar-covered roofs blocks away, and buildings collapsed in on themselves, feeding the inferno.

By the morning of October 9, the fire had reached the city’s business district. Banks, hotels, and department stores crumbled. The Palmer House Hotel, newly opened and hailed as one of the most luxurious in the nation, was reduced to ruins. The courthouse collapsed after its stone walls glowed red-hot.

That afternoon, the fire leapt the main branch of the Chicago River and engulfed the North Side, home to wealthy residences as well as immigrant neighborhoods. Families fled in panic, many carrying only what they could hold. Some sought safety on the shores of Lake Michigan, wading into the water with their belongings, while others crossed bridges that soon caught fire behind them.

By the time rain began to fall on the evening of October 10, the fire had raged for almost 36 hours.

The Scale of Destruction

When the fire at last burned itself out, the scale of devastation was almost beyond comprehension. In just two days, flames had consumed more than three square miles of the city, wiping out 17,500 buildings and leaving nearly 100,000 people, a full third of Chicago’s population, without homes. Property losses were calculated at around $200 million, a sum that would amount to billions in today’s terms.

The official death toll stood at about 300, but many suspected the real number was higher. Entire families vanished in the blaze, their remains reduced to ashes or lost beneath the ruins. Blocks of homes, shops, and churches simply ceased to exist. The bustling commercial district lay in smoldering fragments, government offices had collapsed, and much of the North Side had been reduced to blackened rubble.

Yet amid the destruction, a few stone and brick structures remained upright, standing as improbable survivors. Chief among them were the water tower and pumping station on Michigan Avenue. Scarred but intact, they became symbols of endurance in a city determined to rise again.

Relief and Recovery

In the days after the fire, Chicago faced both a humanitarian crisis and an opportunity. Refugees camped in Lincoln Park, on the prairie west of the city, or in hastily built shantytowns. Churches, schools, and the courthouse that had escaped the blaze became shelters.

Relief poured in from across the United States and even overseas. Donations of food, clothing, money, and building materials arrived by train and ship. The relief effort was coordinated by the Chicago Relief and Aid Society, which distributed supplies and helped families rebuild.

Despite the devastation, the determination to rebuild was immediate. Within weeks, merchants reopened businesses in temporary wooden structures nicknamed “the phoenix stores.” The rebuilding effort was so rapid that within two years, much of downtown had been reconstructed.

Lessons and Legacy

The Great Chicago Fire exposed the dangers of rapid urban growth without adequate fire safety. The city responded by enacting stricter building codes, requiring masonry construction in the central business district, and modernizing the fire department.

The disaster also transformed the city’s identity. Far from being ruined, Chicago rebounded with remarkable speed, attracting architects, engineers, and investors. Out of the ashes arose some of the first steel-frame skyscrapers, and by the 1890s, the city was a model of modern urban design. Hosting the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, Chicago presented itself to the world as reborn, a “phoenix city” risen from fire.

Enduring Symbolism

The Great Chicago Fire remains one of the most dramatic episodes in American urban history. It is remembered not only for its destruction but also for the resilience it inspired. The story of the O’Leary cow endures in popular culture, even as historians emphasize the larger structural causes: drought, flammable construction, high winds, and inadequate firefighting resources.

Today, the Chicago Water Tower stands as a landmark of survival, and the site of the O’Leary barn is home to the Chicago Fire Academy. The fire’s legacy continues to shape how cities prepare for disaster, and how communities define themselves in moments of crisis.