How FDR Changed Thanksgiving to the Fourth Thursday—and Transformed the Modern Holiday Season

Thanksgiving has long been a cherished American tradition, but its date has not always been fixed. For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, most presidents followed Abraham Lincoln’s Civil War-era declaration and celebrated Thanksgiving on the last Thursday of November. However, in 1939—during the Great Depression—President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided to make a change that sparked nationwide debate.

FDR moved Thanksgiving one week earlier, shifting it from the last Thursday to the second-to-last Thursday. Two years later, Congress stepped in with a compromise, officially establishing Thanksgiving as the fourth Thursday of November, the date we still use today.

Why FDR Changed the Date

Roosevelt’s decision was rooted in economics. In the 1930s, the holiday shopping season was much shorter in years when November had five Thursdays. Retailers worried that a late Thanksgiving would reduce sales in a country still struggling to recover from the Depression.

Business leaders approached the Roosevelt administration with a bold idea: move Thanksgiving up by one week. The hope was that a longer holiday shopping season would encourage more spending, boost store revenue, and help stimulate the broader economy.

Roosevelt agreed. In August 1939, he announced that Thanksgiving would be celebrated on the second-to-last Thursday. That year, the shopping season gained an extra seven days.

A Nation Divided—Over a Holiday

The public response was immediate and mixed. About half the states adopted the new date, while the rest stuck with the traditional one. Newspapers joked about “Democratic Thanksgiving” and “Republican Thanksgiving.” Colleges had to alter football schedules. Families ended up celebrating twice—or not at all—depending on which date employers recognized.

The change even inspired a term: “Franksgiving.”

Despite the controversy, the extra week of shopping did provide a modest economic boost. But the confusion across states convinced Congress that a unified national date was necessary.

Congress Steps In

In 1941, after two years of debate, Congress passed a law making Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday in November. This preserved most of the economic benefit of FDR’s change while restoring a predictable schedule for schools, businesses, and communities.

Roosevelt signed the resolution on December 26, 1941. From that point forward, Americans have celebrated Thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday—sometimes the last of the month, sometimes not.

How the Date Shaped Modern Traditions

FDR’s decision—and Congress’s compromise—had lasting effects on American culture and the economy.

A longer holiday shopping season.

Once Thanksgiving was firmly anchored on the fourth Thursday, retailers began to treat the following day as the unofficial start of holiday shopping. Over time, this became Black Friday, now one of the busiest shopping days of the year.

Growth of national holiday travel.

Predictability allowed families to plan far in advance, helping establish Thanksgiving as one of the most traveled holidays in the United States.

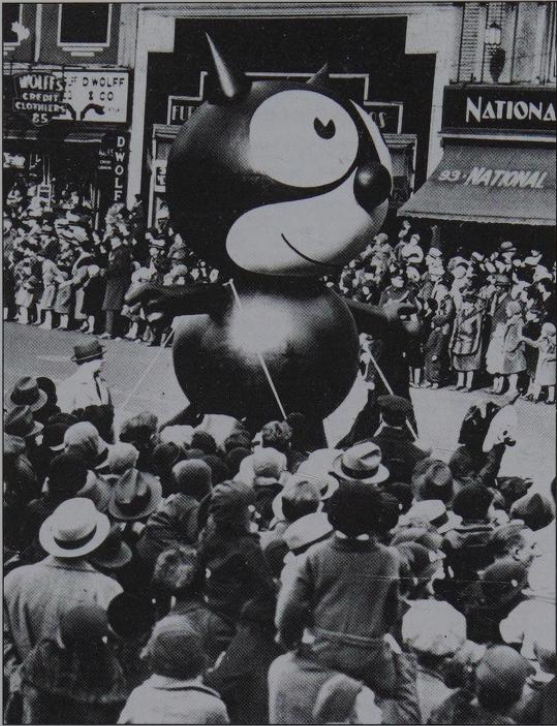

Expansion of parades and public events.

The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, football games, and other national traditions grew more consistent and widely celebrated with a fixed date.

A Tradition Rooted in Both History and Practicality

FDR’s adjustment to Thanksgiving’s timing was not a symbolic change—it was an economic one. In the process, it reshaped how Americans experience the holiday season. Today’s extended shopping period, the rhythm of late-November travel, and the cultural energy around Thanksgiving all trace their origins to that moment in 1939.

The decision shows how traditions evolve not only through heritage but also through practical needs. Thanksgiving, once fluid and flexible, became a fixed part of the American calendar—one shaped by economic realities as much as historical memory.