“Proclaim Liberty”: The First Public Reading of the Declaration of Independence

In July 1776, the streets of Philadelphia were thick with humidity—and tension. Despite the colonies having been at war with Great Britain for over a year, many found the idea of full independence daunting. The American Revolution had begun with pleas for redress and recognition, not with a clear call to sever ties from the Crown.

The Second Continental Congress had gathered delegates from each of the 13 colonies inside the Pennsylvania State House, a two-story red-brick building humming with urgency. These men were lawyers, farmers, merchants, and scholars—ordinary citizens shouldering an extraordinary task. The talk was no longer about compromise. The topic was freedom, and it carried a grave seriousness.

On July 2, 1776, Congress voted for independence. John Adams predicted that the day would be celebrated for generations. But the final wording of the Declaration of Independence, largely drafted by Thomas Jefferson and revised by committee, wasn’t adopted until two days later. The result was a document as radical as it was poetic—one that laid out not just a legal case against King George III, but a philosophical argument for self-rule and the equality of all men.

Now came the hard part: telling the world.

July 8, 1776: The Day the People Heard the Revolution

On the morning of July 8, word spread through Philadelphia that something monumental was about to happen. Town criers, church bells, and handwritten notices summoned citizens to the State House yard, just behind the building where the Declaration had been adopted.

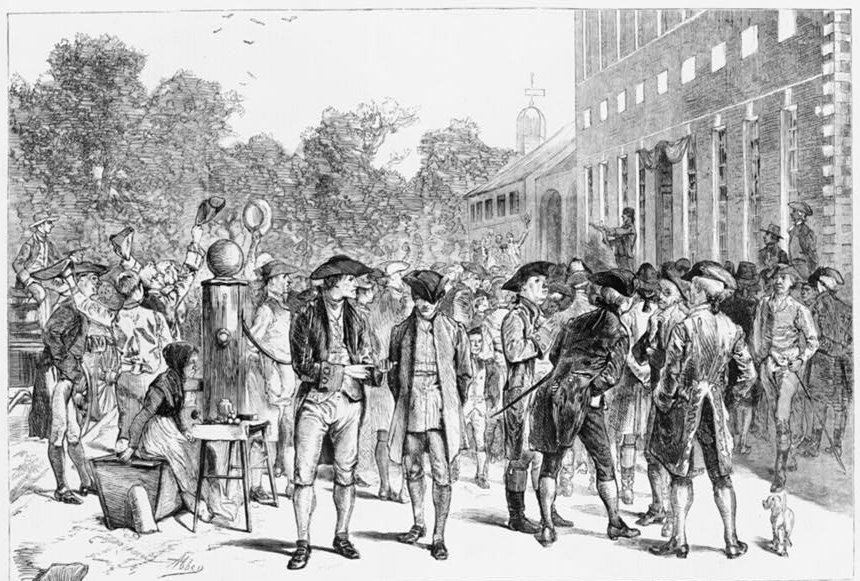

People came by foot, horse, and carriage. Shopkeepers closed their stalls. Carpenters put down their hammers. Mothers carried infants. Enslaved and free Black Philadelphians mingled with soldiers, tradesmen, and Continental Congress clerks. Few knew exactly what they were about to hear, but they sensed that history was about to unfold.

At 12:00 noon, Colonel John Nixon, a local merchant and militia officer, stepped onto a platform and began to read. The document was long, and its legal and philosophical vocabulary dense. But the rhythm of Jefferson’s prose—deliberate, defiant, and clear—cut through the summer air:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…”

For many listeners, these words ignited something profound. They were no longer subjects of a distant king, even if they couldn’t express it. They were citizens of a bold, uncharted republic. Some cried. Others cheered. A few, especially Loyalists who still supported Britain, looked on in horror.

The crowd dispersed, knowing that life had changed. A door had been opened, and there was no turning back.

A Risky Act of Treason and Faith

To modern ears, the Declaration is a revered document, read on the Fourth of July and tucked away behind bulletproof glass in the National Archives. But in 1776, it was a dangerous manifesto. Reading it aloud in public was an act of rebellion punishable by imprisonment—or worse.

Colonel Nixon, the man who read it aloud, knew what he was risking. So did the crowd. A British army wasn’t far away, and their arrival could mean martial law, retaliation, or imprisonment for anyone seen as aiding the rebel cause. The reading served as more than just a ceremony; it marked a crucial moment.

And yet, the people came. Not just out of curiosity, but because they believed in the possibility of something new. For them, the words weren’t just lofty ideals—they were a lifeline to a future where farmers could own land without paying tribute to an empire, where craftsmen could vote on their own laws, and where their children might be born free.

Carried by Horse and Press: How the Words Spread

Following the first reading, copies of the Declaration were quickly printed by John Dunlap, the official printer of Congress. These early editions, known as Dunlap Broadsides, were typeset and run off the press on the night of July 4–5, likely with the ink still damp when they were dispatched to the colonies.

Couriers and post riders, many of them veterans of Paul Revere-style missions, galloped across the colonies carrying copies to governors, militia commanders, town halls, and newspapers. In each location, a similar ritual played out: townspeople would gather, the local leader would ascend the steps of a courthouse or church, and the Declaration would be read aloud to a crowd that waited with breath held.

In Boston, the words were read from the Old State House, not far from where the Boston Massacre had taken place six years earlier. In Savannah, a parade followed the reading. In Charleston, cannons boomed in celebration. New York City’s crowd famously tore down a statue of King George III after hearing the Declaration, melting the lead into musket balls for the Continental Army.

This wasn’t just information-sharing—it was a shared moment of civic awakening. Across hundreds of miles, thousands of people experienced the same words, the same call to action, and the same flicker of hope.

Legacy of a Summer Day

Each year, on July 8, Philadelphia recreates that moment with a live reading at Independence Hall. But what made the original reading remarkable was not just the document—it was the people. Farmers, widows, printers, dockworkers, and apprentices heard that they were equal, that they were free, and that they had the right to shape their own destiny.

The Declaration’s first public reading was not a conclusion. It was a beginning. The war would grind on for seven more years. Freedom would come slowly, unevenly, and incompletely—especially for enslaved people, Indigenous communities, and women, all of whom were excluded from the promises made that day.

But the ideals spoken on July 8, 1776, lit a torch that still burns. They were imperfectly realized, but relentlessly pursued. And that pursuit—the belief that liberty is worth fighting for—has echoed through every civil rights movement, every suffrage campaign, and every generation since.