What Caused the French and Indian War?

From the founding of Jamestown in 1607 through the 1750s, the English colonies continued to grow, both in the number of colonies and overall population. Settlements that started near the coast soon spread west to create other cities and settlements inland. The English colonies grew from a population of a few hundred settlers in the early 1600s to over two million by 1770. As more people moved to the colonies to take advantage of new opportunities, they needed more space to establish homes and farmland to support their families. This creates a consistent effort to build new settlements further west toward and eventually beyond the Appalachian Mountains.

https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/colonialbostonpops.pdf

It is important to remember that until July 1776, English colonists in North America considered themselves British citizens and loyal subjects of the English king. They expected, as British citizens, to have the same rights as citizens living inside the British Isles. The colonists had a history of democratic elections and intrinsic rights protected under the English Bill of Rights (1689). Among other rights, all British citizens were guaranteed freedom of speech and the freedom of taxation without the consent of Parliament. For colonists, these rights were ingrained into them as British citizens; simply moving to the New World did not remove their rights.

During the latter half of the colonies’ development, the king of England was George II (reign 1727-1760). He was born in North Germany and did not become the British King until he was 44. As he lived most of his life on the European continent, George II was never interested in British domestic affairs, nor was he interested in being directly involved with the colonies. Thus, each colony operated independently from Great Britain.

Courtesy of a National Portrait Gallery, London

The absence of formal influence from Britain allowed the colonies to develop their own democratic structures. The Virginia Colony, for example, created a representative legislature, the House of Burgesses, whose members were selected by popular election to represent their constituents. Because the colonists did not have direct representation in the British Parliament, their colonial governments were the only way they could communicate with Parliament.

Despite not being on the European continent, the colonies had to continually contend with pressures and military conflict from other European powers. By the 1750s, English colonies in North America were surrounded by other European powers, with the French to the North, in modern-day Canada, and the Spanish to the South, in modern-day Florida. As a result, there was always the potential for foreign invasion. In 1754, Benjamin Franklin proposed a plan—the Albany Plan of Union—to unite the colonies for their common defense. This was the first time coming together for a common purpose had ever been proposed. Franklin’s plan was ultimately rejected because the colonists believed it was the duty of the king and the British military to protect the colonies from attack. Additionally, colonists did not want to be taxed by a unified colonial government; they did not want to create a new government that, they worried, would have too much power and also remove some of the sovereign power of the colonies.

As the English colonies continued to grow and colonial populations pushed further west, hostilities began growing in the Ohio River Valley. The French presence at Fort Duquesne (in modern-day Pittsburgh) effectively halted English western expansion. The Ohio Valley was rich for beaver hunting, and the fur trade made many colonists wealthy. Neither the French nor the English wanted to lose access to these rich hunting grounds. Control of these lands would also give the French access to the Mississippi River, which connected their northern settlements (in modern-day Canada) to their southern territory in New Orleans.

This westward expansion of American colonies led to the conflict between English and French settlers—a conflict that eventually escalated into the French and Indian War. While some English colonists believed this fight against the French was one for the British army alone, colonists themselves did participate in the war; in fact, future American hero George Washington saw his first combat during the French and Indian War as a British officer. He was not as successful then as he would be later; on July 3, 1754, Washington was forced to surrender to a larger French force.

The French and Indian War was the American theater of the larger Seven Years’ War that played out in Europe between British, French, and Spanish forces.

The British ultimately won the French and Indian War. Their victory gave the British unquestioned control over the colonies. However, it also created new tensions between the king and the colonies. The British believed the colonies refused to contribute men, money, and resources to help the war effort. Conversely, the colonists believed they’d done all they needed to do as British citizens. This disagreement over the colonists’ perceived lack of participation during the French and Indian War, and who would pay the war expenses, began pushing the colonies toward independence.

In 1760, George II died. He was succeeded by his grandson George III. Unlike the disinterested George II, George III was born and raised in England and saw himself as British; he asserted more control over all domestic and colonial issues. The king believed the colonies needed to help cover the French and Indian War costs. His involvement creates new conflicts between the colonies and Britain. For example, King George III issued the Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited colonists from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains. This created tension between the growing colonies over scarce land and natural resources.

Courtesy of a National Portrait Gallery, London

There had always been tension between colonial leaders and settlers about western expansion. Colonial leadership knew they were encroaching on Native American lands and would likely create unwanted conflict with them if they continued to push westward. On the other hand, settlers risked their lives to come to the New World and did not want to be told they could not have land to settle.

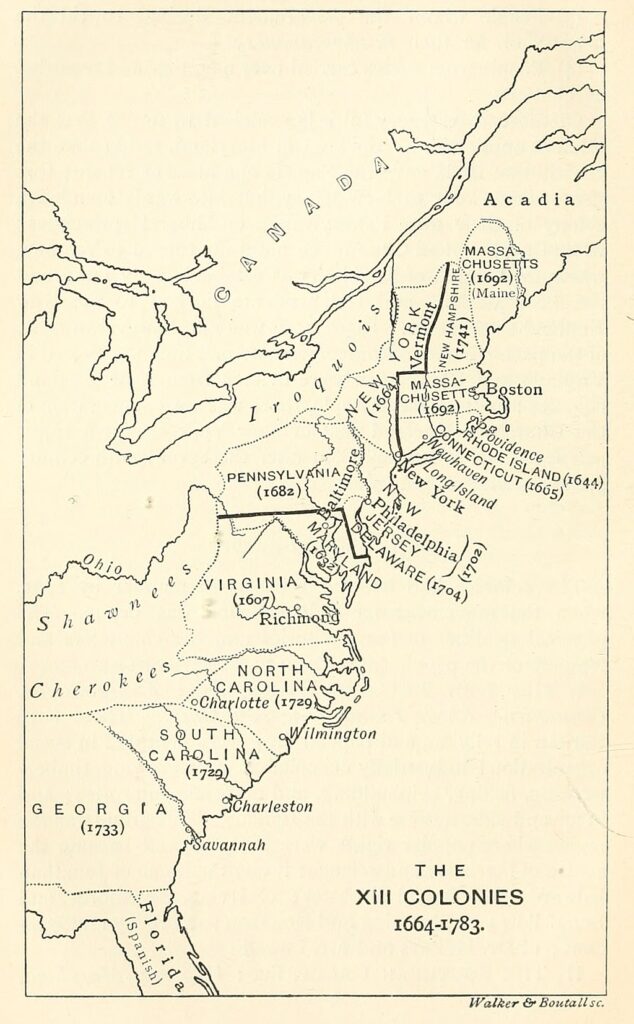

From English Colonization and Empire. John Murray, London 1901. Public Domain

There had always been stress between colonial leaders and settlers about western expansion. Colonial leadership knew that settlers were encroaching on Native American lands and would likely create unwanted conflict with Native Americans if they continued pushing westward. On the other hand, settlers risked their lives to come to the New World and did not want to be told that they couldn’t settle new land.

The Proclamation of 1763 created colonial hostility toward George III because, to the colonists, the proclamation showed that the king did not care about their needs. Moreover, they did not believe they were receiving any benefits from the French and Indian War victory if they were not granted additional land to settle.

The pressures placed on the colonists by the British Parliament and George III—pressures such as limiting where colonists could settle and, eventually, Parliament’s approval of additional taxes—caused the colonists to begin to question their loyalties to Britain and George III.