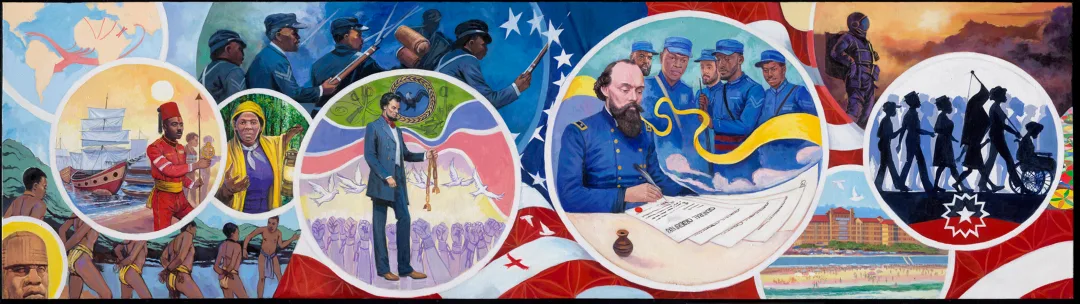

Juneteenth: The Long Road to Emancipation and the Meaning of Delayed Freedom

On June 19, 1865, Union Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, at the head of approximately 2,000 federal troops. His mission was not only to restore federal authority in the final holdout of the defeated Confederacy but to enforce a long-overdue mandate: the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. From the steps of Ashton Villa and other public locations, Granger issued General Order No. 3, which began:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

That order marked the first public and enforceable declaration of freedom for over 250,000 enslaved individuals in Texas—arguably the last region of the Confederacy where slavery had persisted in full operation despite its formal abolition on paper. This moment, now commemorated as Juneteenth, represents the delayed but definitive implementation of the Emancipation Proclamation and has come to symbolize the complex, uneven, and unfinished process of emancipation in the United States.

The Emancipation Proclamation and Its Limits

President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, effective January 1, 1863, was a wartime executive order that declared enslaved persons free in all rebelling Confederate states. However, its legal reach was constrained. It did not apply to slaveholding border states that remained in the Union, nor could it be enforced in Confederate areas still under rebellion and not occupied by Union forces. Its true impact came in tandem with military victories and the gradual occupation of Southern territory by Union troops.

Texas, geographically remote and largely untouched by significant combat, had become a refuge for slaveholders. Many planters moved to Texas with enslaved people during the war, believing they could continue their operations unimpeded. By war’s end, the institution of slavery in Texas was thriving, even as it had collapsed elsewhere.

Granger’s Arrival and General Order No. 3

Granger’s June 19th proclamation did not merely inform enslaved people of their legal status—it enforced it. General Order No. 3 explicitly stated that “all slaves are free” and added that this new freedom carried both personal and economic implications. It clarified that former masters and slaves were now considered employers and hired laborers, advising that newly freed individuals remain “quietly at their present homes” and work for wages.

The order was met with a mix of celebration, disbelief, and confusion. While some slaveholders resisted the announcement, others attempted to delay its effects, continuing to exploit enslaved labor for weeks and months afterward. In some cases, freedom was violently contested. Nevertheless, Juneteenth became the moment freedom was made real for many African Americans in Texas.

The Aftermath: Celebrating Freedom Amid Oppression

The initial celebrations were spontaneous and jubilant. Freed people gathered to sing spirituals, read the Emancipation Proclamation aloud, and reflect on the meaning of freedom. These observances continued annually and took on a formal name—Juneteenth, a portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth.”

Despite being born out of liberation, Juneteenth traditions developed under the shadow of new forms of repression. The end of slavery was followed by the rise of Black Codes, convict leasing, and, later, the institutionalized racism of the Jim Crow era. In many Southern states, Juneteenth celebrations were actively discouraged or excluded from public spaces. In response, African American communities often purchased land, such as Houston’s Emancipation Park, to hold their own observances.

Juneteenth became a day of remembrance, education, resistance, and cultural affirmation. Celebrations featured prayer services, public readings, family reunions, and parades. These gatherings reinforced a sense of collective memory and identity, even when broader American society refused to recognize the holiday.

From Local Commemoration to National Recognition

In 1980, Texas became the first state to recognize Juneteenth as a state holiday. Activist Opal Lee, often referred to as the “grandmother of Juneteenth,” played a pivotal role in building national momentum for federal recognition through marches, petitions, and public education.

In the wake of the 2020 protests for racial justice, sparked by the murder of George Floyd, Juneteenth gained renewed national attention. Calls for federal recognition reached a critical mass. On June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act into law, making Juneteenth the 11th federal holiday in the United States.

This act was both a symbolic and substantive gesture, acknowledging not just the end of slavery but the historical neglect of the African American experience in public memory and education.

Why Juneteenth Matters Today

Juneteenth represents more than a single day of emancipation—it is a meditation on the nature of freedom in America. It calls attention to the delayed justice and systemic barriers that have characterized the Black American experience. It reminds us that emancipation did not guarantee equality and that freedom, without access to justice, education, land, and the franchise, is fragile.

In schools, Juneteenth opens pathways for teaching Reconstruction, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, and the legacies of racial injustice. In communities, it provides an occasion to center African American voices, stories, and contributions to the nation.

Importantly, Juneteenth is a living history, not a static commemoration. It demands that we remember the enslaved who waited years to hear freedom’s proclamation and that we recognize those who continue to struggle for full participation in American democracy.

Conclusion: A Freedom Still in the Making

Juneteenth does not mark the end of slavery in a singular, celebratory sense—it marks the moment when the idea of freedom finally arrived in the most remote parts of the American South. It is a testament to the resilience of a people and the power of historical memory.

As the nation continues to grapple with the meaning of liberty, equality, and justice, Juneteenth stands as both a celebration and a challenge—a celebration of how far we’ve come and a challenge to complete the work that remains.