The Development of the 8-Hour Workday: A Century in the Making

The 8-hour workday is something many of us take for granted today, but it wasn’t always the standard. It took more than half a century of struggle and activism for this idea to become a reality in the United States. The journey toward the 8-hour workday began in the 19th century and culminated in the early 20th century under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

National Labor Union’s Established in 1866

On August 20, 1866, the National Labor Union (NLU) made history by becoming the first national organization to call for an 8-hour workday. At the time, it was common for workers, including children, to labor 10 to 16 hours a day in dangerous and exhausting conditions. The NLU recognized that such long hours were unsustainable and harmful to children and adults’ health and well-being. They argued that workers needed more time for rest, family, and personal pursuits.

Early Struggles and Partial Successes

The campaign for an eight-hour workweek persisted among workers with the advancement of the Industrial Revolution and into the 20th Century. Labor organizations organized to seek improved working conditions, and as a result, strikes, protests, and rallies became commonplace. Although some businesses or industries agreed to reduce labor hours, there was no national standard in place.

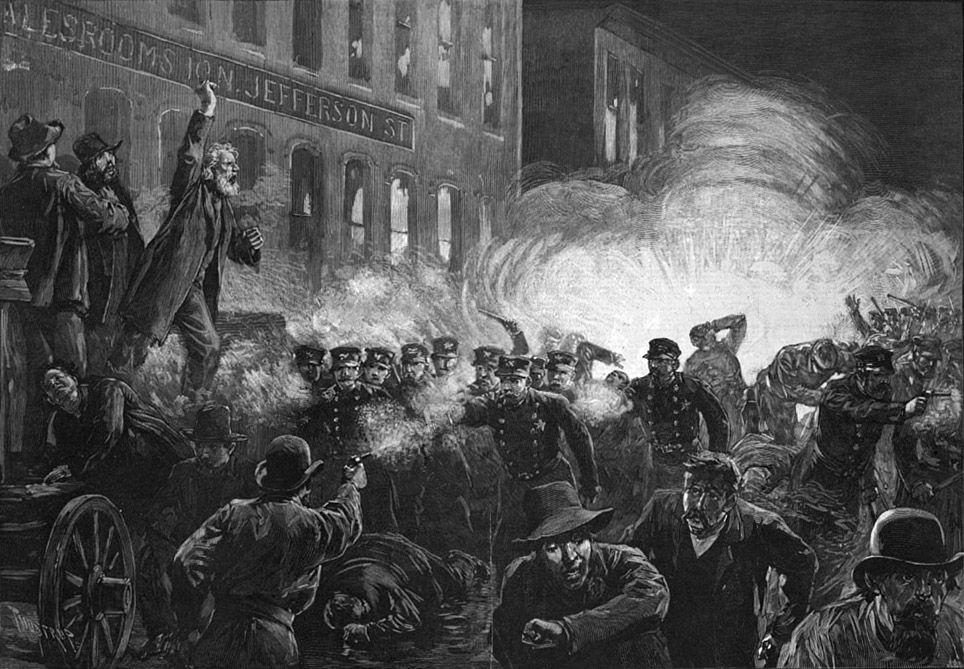

The Haymarket Affair in Chicago in 1886 was one of the most prominent occasions of this conflict. When a bomb was thrown at police during a nonviolent demonstration in favor of an eight-hour workday, three police officers and bystanders were killed. The event brought about a national campaign against labor unions, but it also brought attention to the significance of the eight-hour workday movement.

The Turning Point: The National Industrial Recovery Act

67 years after the initial effort, the 8-hour workday became a national standard in the United States during the Great Depression in 1933, largely due to the efforts of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. As part of his New Deal program to revive the economy, Roosevelt signed the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) into law. The NIRA included a provision that established a maximum work week of 40 hours, effectively creating the 8-hour workday as we know it today.

The NIRA was a response to the economic crisis, aiming to reduce unemployment by spreading work among more people. It also sought to improve working conditions and wages, recognizing that fair labor standards were essential to a healthy economy. Although the NIRA was later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935, its principles were preserved in subsequent legislation, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which solidified the 8-hour workday and a 40-hour workweek as the national standard.

A Legacy of Struggle and Victory

The development of the 8-hour workday is a testament to the power of collective action and the importance of labor rights. Today, the 8-hour workday ensures that workers have the time they need to live balanced and fulfilling lives.

Works Cited

History.com Editors. (2020). Labor movement. History. https://www.history.com/topics/19th-century/labor

The Library of Congress. (n.d.). The National Industrial Recovery Act. https://guides.loc.gov/national-recovery-administration

U.S. Department of Labor. (n.d.). Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938: Maximum struggle for a minimum wage. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/flsa