The Other Day of Independence: What Really Happened on August 2, 1776

Ask most Americans when the Declaration of Independence was signed, and the answer will almost always be July 4, 1776. That date is etched into our national memory. It appears on the document itself, is marked each year with fireworks and celebration, and is taught as the birthday of the United States. However, like many foundational stories, the actual timeline is more complex.

The truth is that most of the signers of the Declaration of Independence did not actually sign the document on July 4. That famous act took place later, on August 2, 1776, and even then, not all fifty-six signers were present. Understanding why requires a deeper look at the fragile and uncertain world of revolutionary politics in the summer of 1776.

A Declaration in Stages

On July 2, 1776, after more than a year of petitions, skirmishes, and rising tensions, the Second Continental Congress voted to declare independence from Great Britain. The vote followed Richard Henry Lee’s resolution, introduced in early June, which boldly proposed that the American colonies “are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.”

The vote passed after intense debate, and with it, the colonies took a final, irreversible step. John Adams famously believed that July 2 would become the most significant day in American history. In a letter to his wife Abigail, he predicted future generations would celebrate it with “pomp and parade… bonfires and illuminations.” He was off by two days.

Two days later, on July 4, the Congress formally approved the wording of the Declaration of Independence. The document had been drafted largely by Thomas Jefferson, who worked closely with John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, as well as Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston, the other members of the drafting committee. Congress made several revisions to Jefferson’s draft, trimming about a quarter of the original text and removing several passages, including a pointed condemnation of the British monarchy’s role in perpetuating the transatlantic slave trade.

Once finalized, the text was sent to Philadelphia printer John Dunlap, who produced approximately two hundred broadside copies that very night. These are now known as the Dunlap Broadsides, and they represent the first published version of the Declaration. These copies were distributed quickly to the thirteen colonies, to military leaders such as General George Washington, and to international representatives. They were also read aloud in public places and reprinted in colonial newspapers.

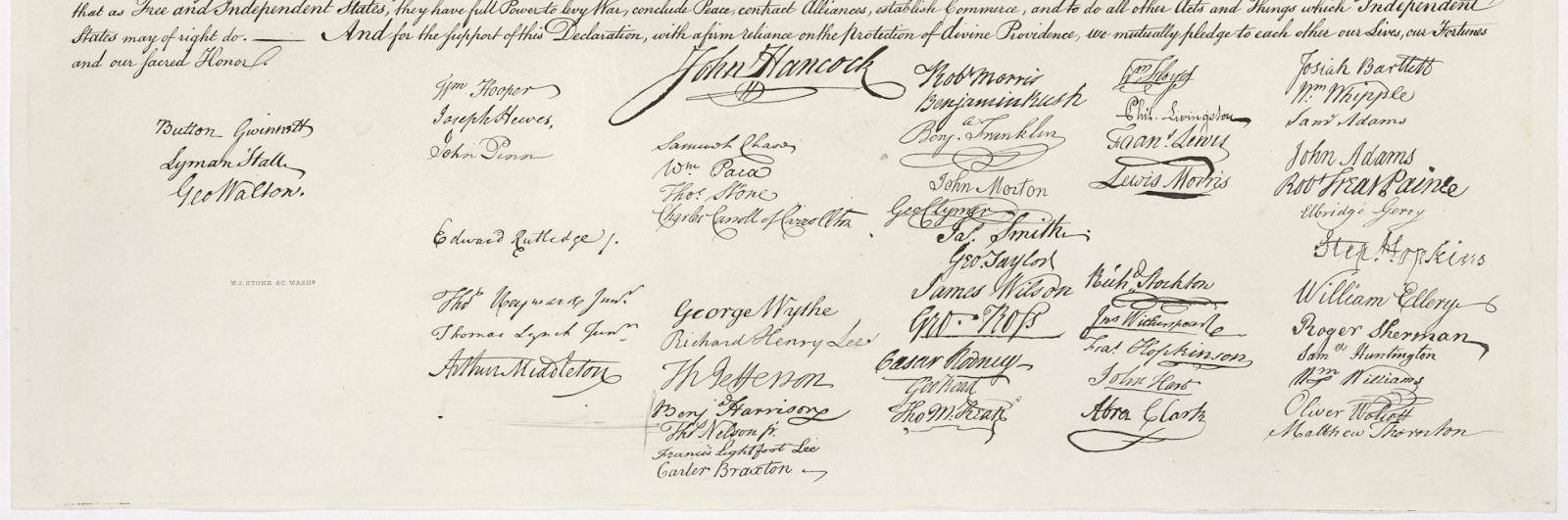

But these printed copies contained only the names of John Hancock, as President of Congress, and Charles Thomson, the Congress’s Secretary. The familiar image of dozens of signers gathered around a single document had not yet come to pass.

The Parchment and the Signers

The iconic handwritten version of the Declaration, now on display in the National Archives, was created several weeks later. This version was written on high-quality parchment by Timothy Matlack, a Philadelphia scribe and assistant to Charles Thomson, who was well known for his fine penmanship.

On August 2, 1776, the Congress reconvened, and the engrossed parchment copy was presented for signing. Most of the delegates who had voted for or now supported independence were there and signed the document.

However, the process of signing was not instantaneous, nor was it entirely complete on August 2. Several delegates signed later, either because they were not present in Philadelphia at the time or because they were newly appointed members of Congress. For example, Matthew Thornton of New Hampshire, who was elected to Congress in September, did not sign until November. Others, such as Thomas McKean of Delaware, appear to have signed much later still, possibly as late as 1781, although the historical record is somewhat unclear.

A few men whose names appear on the Declaration were not present for the July 4 vote and did not participate in the initial debates. At the same time, a handful of delegates who voted for independence never signed the final document. This is partly because the Declaration became a symbolic statement for the ages, and Congress eventually allowed new members to add their names as a gesture of unity.

The Risks and the Realities

Signing the Declaration was no mere formality. Each man who picked up the quill knew he was committing an act of treason in the eyes of the British Crown. The war was already underway, and British forces had just landed a massive army on Staten Island, preparing to launch an invasion of New York.

The delegates signed, knowing they were putting their lives, fortunes, and families at risk. John Hancock’s large, ornate signature at the top of the list is often said to reflect a bold defiance, although the famous line about making his name big enough for King George to read without glasses may be apocryphal. However, the sentiment effectively conveys the gravity of the situation. These were not just words on parchment; this was an act of rebellion.

Why We Remember July 4

The reason we commemorate July 4 rather than August 2 has less to do with the signing and more to do with symbolism. July 4 was the date that Congress adopted the final text. That was the day the colonies, in the eyes of their representatives, officially declared their independence from Great Britain.

By the time Americans began celebrating their independence in earnest in the 1780s and 1790s, July 4 had already taken hold as the moment that marked the break with Britain. Public readings, anniversary parades, and even early fireworks were scheduled to honor the date printed at the top of the Declaration. Over time, the myth of the signing on July 4 hardened into national memory, despite the actual events unfolding more slowly and less dramatically.

A Reminder of Process, Not Just Product

The story of August 2 reminds us that the American Revolution was not a single moment of unity, but rather a series of events that unfolded over time. It was a complex and uncertain process, full of debate, delay, and risk. The Declaration of Independence was not born in a single day. It was debated, revised, printed, distributed, and only then signed, not in one sweeping act, but over time.

The signatures on the parchment do not just mark the founding of a new nation. They represent the courage to commit to it publicly and the hope that a scattered collection of colonies could unite under a common cause.

So, while we rightly celebrate the Fourth of July, we might also remember August 2, the day when the promise of the Declaration became not just a vote or a proclamation, but a personal commitment etched in ink by men who risked everything to make their vision a reality.