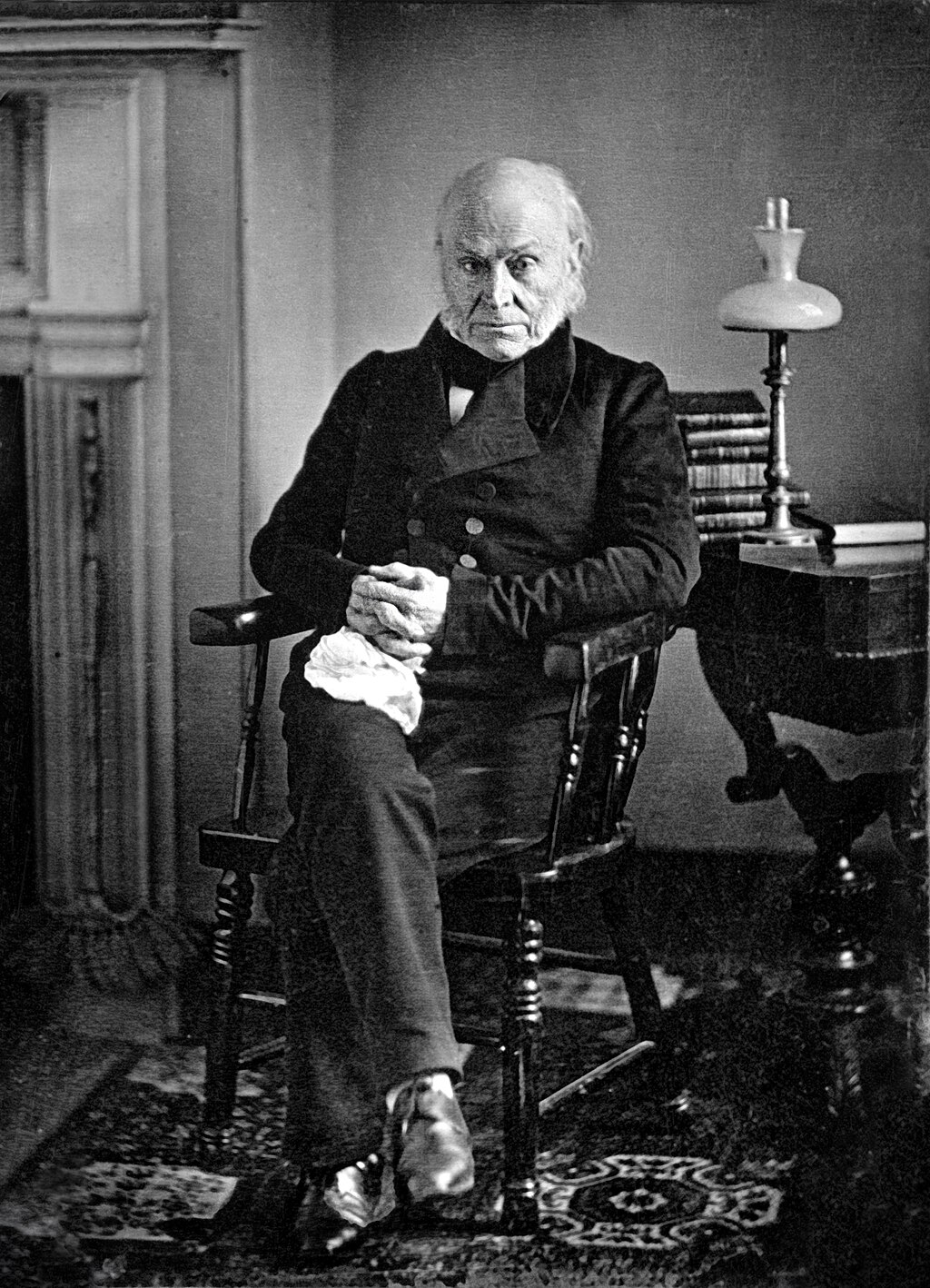

John Quincy Adams: Statesman, President, and Defender of Principle

John Quincy Adams was more than just America’s sixth president. He was a lifelong public servant, a master diplomat, and one of the most intellectually gifted leaders in U.S. history. Born into the founding generation, Adams played a pivotal role in shaping the country during its early decades. He spoke out for national unity, constitutional limits, and moral responsibility—even when it made him unpopular.

Early Life and Education

John Quincy Adams was born on July 11, 1767, in Braintree, Massachusetts (now Quincy), the son of John and Abigail Adams. His parents raised him to value education, civic duty, and personal integrity. During the American Revolution, young Adams accompanied his father on diplomatic missions to Europe. These experiences gave him a rare early education in international affairs, languages, and Enlightenment political thought.

He was fluent in French and Dutch by his teens and later learned German and Latin. Adams studied at institutions in Paris, Amsterdam, and Leyden before returning to the United States. He graduated from Harvard in 1787 and practiced law briefly, but his career would quickly turn toward diplomacy and politics.

Early Diplomatic Career

In 1794, at just 26 years old, President George Washington appointed Adams the U.S. minister to the Netherlands. Over the next two decades, he served in increasingly important diplomatic posts. He was minister to Prussia (1797–1801), Russia (1809–1814), and the United Kingdom (1815–1817). In each role, Adams gained a reputation for discipline, intelligence, and independence. Even political enemies respected his skills.

His most significant achievement during this time was serving as the lead negotiator of the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, which concluded the War of 1812. The treaty did not resolve all the causes of the war, but it restored peace between the U.S. and Britain without territorial loss—a major diplomatic win.

Secretary of State (1817–1825)

Adams’s term as secretary of state under President James Monroe is widely considered one of the most effective in American history. He played a key role in crafting the Monroe Doctrine (1823), which declared the Western Hemisphere closed to future European colonization. Although President Monroe announced the doctrine, it was John Quincy Adams who wrote the key language and defended it as a declaration of American independence in foreign policy.

Adams also negotiated several important treaties. The most notable was the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819 with Spain, which secured Florida for the United States and settled a boundary with Spanish territory in the West. He also helped define America’s border with Canada through negotiations with Britain.

The Election of 1824 and the “Corrupt Bargain”

The presidential election of 1824 was the first where all candidates claimed to be “Republicans,” following the collapse of the Federalist Party. The race had four major contenders: Adams, Andrew Jackson, William H. Crawford, and Henry Clay. Jackson won a plurality of the popular and electoral vote but not a majority. Under the 12th Amendment, the House of Representatives had to make a decision.

Adams won the House vote with Clay’s support, and soon after, Adams appointed Clay as secretary of state. Jackson and his allies accused them of a “corrupt bargain,” charging that Adams had bought Clay’s support with a promise of office. There’s no direct evidence of a deal, but the accusation haunted Adams’s presidency and helped Jackson build a strong opposition movement.

Presidency (1825–1829)

As president, Adams had ambitious plans. He supported national infrastructure projects, including roads, canals, and scientific institutions. He called for the creation of a national university, a naval academy, and increased support for the arts and sciences. He believed the government had a role in improving society and fostering knowledge.

But Adams lacked political allies. The Jacksonian coalition in Congress blocked much of his agenda. He refused to use patronage to win support and rejected popular campaigning, believing it was beneath the dignity of the office. As a result, his presidency was largely ineffective in passing major laws.

In 1828, Jackson defeated Adams in a bitter, personal campaign that signaled the rise of a new kind of populist politics. Adams left the office deeply discouraged.

Return to Congress and Fight Against Slavery (1831–1848)

In a remarkable turn, Adams returned to public service as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts in 1831. He served there for 17 years, longer than any other former president has served in federal office.

In the House, Adams became a vocal opponent of slavery. He repeatedly introduced petitions to end slavery in Washington, D.C., and challenged the “gag rule,” which banned such petitions. He saw the rule as a violation of the First Amendment and fought it for eight years until it was repealed in 1844.

Adams also played a central role in the Amistad case. In 1839, a group of enslaved Africans took control of a Spanish ship off the coast of Cuba. After the ship was captured, the case reached the Supreme Court. In 1841, Adams—then in his 70s—argued the case before the Court and won. The captives were freed.

Death and Legacy

On February 21, 1848, John Quincy Adams suffered a stroke on the floor of the House while answering a question about the Mexican-American War. He died two days later in the Speaker’s Room of the Capitol. His final words were, “This is the last of Earth—I am content.”

Today, Adams is remembered as a man of principle and intellect. He was not a successful president by legislative standards, but he lived by his convictions. He believed in the Constitution, in civil liberties, and in using government to improve society. He fought against slavery long before it was popular to do so and defended rights even when it meant standing alone.

John Quincy Adams was not a popular president, but he was a principled one. He believed in service, truth, and the power of government to do good. He read widely, wrote daily, and worked tirelessly for what he felt was right, even when it made him enemies.

His career reminds us that public service is not always about winning. Sometimes, it’s about maintaining your integrity, even in the face of opposition.