Marquis de Lafayette: The Hero of Two Revolutions

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, was born on September 6, 1757, in the rugged Auvergne region of south-central France. He came from a long line of military aristocrats, and his family’s legacy was inseparable from service to the French crown. His father, Michel Louis Christophe Roch Gilbert du Motier, served as a colonel in the French army and heroically lost his life at the Battle of Minden in 1759 due to British artillery fire. Lafayette was only two years old.

His mother, Marie Louise Jolie de La Rivière, raised him in Paris and at the family’s estate of Chavaniac, ensuring that he received a classical education befitting his noble station. Yet his early life was shadowed by loss; both parents died before he reached adolescence, leaving him heir to one of the wealthiest fortunes in France.

Lafayette received his education at the Collège du Plessis in Paris, where he received training in rhetoric, philosophy, and Enlightenment thought. He was drawn to the ideals of liberty and reason espoused by writers such as Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Rousseau. His marriage at sixteen to Adrienne de Noailles, daughter of the Duc d’Ayen, placed him among the highest circles of French nobility.

At court, people admired his manners and youthful charm, yet he found the aristocratic life suffocating. Even as a teenager, Lafayette’s letters revealed a restless mind, one that longed for purpose beyond titles and privilege. That purpose would soon come from across the Atlantic.

A Young Idealist Drawn to Revolution

In 1775, news reached Europe of armed conflict between British soldiers and American colonists at Lexington and Concord. To many young Frenchmen, the American cause represented the Enlightenment’s boldest experiment: a test of whether a people could govern themselves by reason and consent rather than divine right.

For Lafayette, the idea of defending liberty was irresistible. “My heart,” he wrote, “was enlisted before I set sail.” The French government forbade its officers from aiding the American rebels, but Lafayette’s conviction was stronger than royal command. At just nineteen, he purchased and outfitted a ship, the La Victoire, with his own funds and secretly sailed for the New World.

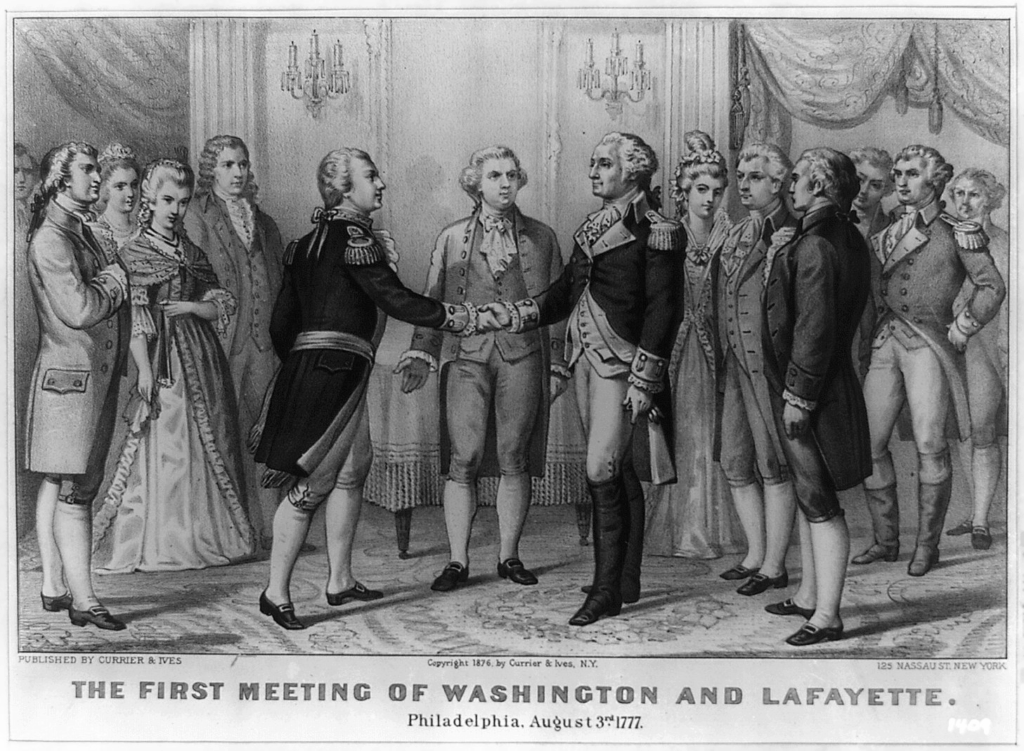

After a perilous Atlantic crossing, he landed near Charleston, South Carolina, in June 1777. Making his way north, he presented himself to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, a foreign nobleman offering to serve without pay. Many delegates doubted his sincerity, but George Washington, always a judge of character, recognized in the young Frenchman a genuine ally. Lafayette was commissioned a major general in the Continental Army, an extraordinary appointment for someone barely twenty years old.

The General and the Commander-in-Chief

The bond between George Washington and Lafayette became one of the deepest personal relationships of the Revolutionary era. Washington, more than twice Lafayette’s age, saw in him the son he never had. Lafayette, in turn, regarded Washington as a mentor, a moral exemplar, and a father figure.

At the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777, Lafayette’s courage became legendary. When the American line faltered under British attack, he rode forward to rally the troops, taking a musket ball in the leg. He refused to leave the field until order was restored. Washington later commended his “bravery and coolness in the face of danger,” and from that day, Lafayette’s loyalty to him was unshakable.

He spent the brutal winter of 1777–78 at Valley Forge, sharing in the hardships of the army and earning the affection of the soldiers. His presence helped sustain morale and foster unity among troops who saw in him proof that their struggle inspired idealists abroad.

Over the next years, Lafayette’s strategic insight matured. At the Battle of Monmouth (1778), he led an advance division with skill and restraint, helping Washington transform the Continental Army into a disciplined force capable of standing against the British. His coordination with French naval forces in Rhode Island that same year demonstrated his growing sophistication as both soldier and diplomat.

Yet perhaps his greatest service to the Revolution came not on the battlefield but through his pen and influence. His correspondence with French leaders Count de Vergennes, Benjamin Franklin, and even King Louis XVI helped convince France that the American cause was both just and winnable. In Lafayette’s words, “Humanity has won its cause; liberty has a country.”

The Return to France and the Turning Point at Yorktown

In 1779, Lafayette returned to France as both a hero and an advocate. The public and courtiers welcomed Lafayette despite his official reprimand for disobeying the King’s earlier orders. He used his position to lobby relentlessly for direct military aid to the Americans. His charisma and personal relationships, especially with Queen Marie Antoinette, helped soften royal resistance.

His efforts bore fruit. In 1780, France dispatched a 6,000-man army under General Rochambeau and a fleet under Admiral de Grasse to cooperate with Washington’s forces. Later that year, Lafayette returned to America with the thrilling news of finally securing full French support.

Placed in command of American forces in Virginia, Lafayette confronted British General Charles Cornwallis in a series of strategic maneuvers known as the “race to the Dan.” Outnumbered, he avoided confrontation, instead harassing and isolating the British army. His tactics forced Cornwallis to fortify his position at Yorktown, a decision that proved fatal.

In October 1781, as Washington and Rochambeau’s combined forces encircled Yorktown, Lafayette’s troops held the critical northern line, blocking escape routes. The French navy cut off a retreat by sea. After a three-week siege, Cornwallis surrendered. The Siege of Yorktown ended the war for independence and cemented Lafayette’s place in American history.

As the defeated British marched out to lay down their arms, Lafayette stood beside Washington, a young aristocrat who had earned the gratitude of a nation not his own.

A Revolutionary in France

Lafayette returned to France in 1782 as a transatlantic hero. He had defied royal orders, fought for republican liberty, and returned triumphant. For the French public, he embodied the Enlightenment ideal, proof that noble birth and democratic principle could coexist.

In the years leading up to the French Revolution, Lafayette became a leading advocate for reform. Elected to the Estates-General in 1789, he sided with the reformist Third Estate and soon became commander of the newly formed National Guard of Paris. His task was monumental: to maintain order amid rising chaos and steer France toward a constitutional monarchy.

Lafayette drafted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted in August 1789. Modeled on both the American Declaration of Independence and Enlightenment philosophy, it proclaimed that “men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” It remains one of the foundational documents of human rights in the modern world.

However, Lafayette’s moderation made him vulnerable. Royalists viewed him as a traitor, while radicals considered him a conservative. As violence engulfed Paris from the storming of the Bastille to the rise of the Jacobins, he found himself increasingly isolated. In 1791, he defended the royal family from a mob at the Tuileries Palace, a gesture that doomed his popularity with the revolutionary masses.

When he denounced the growing extremism of Robespierre and the Jacobins, he was declared an enemy of the people. Forced to flee France in 1792, he was captured by Austrian forces and imprisoned.

Imprisonment and Endurance

Lafayette spent nearly five years in captivity, held at Olmütz under brutal conditions. Isolated, ill, and uncertain of his fate, he nonetheless refused to renounce his principles. He was eventually joined by his devoted wife, Adrienne, who endured her own imprisonment during the Reign of Terror and narrowly escaped execution through the intervention of George Washington and Alexander Hamilton.

Her arrival at Olmütz transformed his captivity into an act of shared endurance. “You have brought me liberty in my chains,” he told her. Their reunion became a symbol of fidelity and courage admired throughout Europe.

His release in 1797 came through the diplomacy of Napoleon Bonaparte, who saw political advantage in restoring the imprisoned hero. Yet Lafayette, though grateful, remained wary of Napoleon’s authoritarian ambition. When offered a position in Napoleon’s government, Lafayette declined, saying, “I have loved liberty too well to be its servant.”

Return to Public Life and Visit to America

After the fall of Napoleon, Lafayette returned to France as a statesman of conscience rather than ambition. He was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, where he spoke eloquently for constitutional monarchy, civil rights, and the abolition of slavery.

In 1824, at the invitation of President James Monroe, Lafayette embarked on a grand tour of the United States to mark the nation’s 50th anniversary. His arrival ignited a wave of national celebration unparalleled in the early republic. Cheerful crowds, parades, and addresses of gratitude greeted him from New York to New Orleans. People named cities, counties, and schools after him: Lafayette, Louisiana; Fayetteville, North Carolina; and LaGrange, Georgia.

The journey was more than a sentimental reunion; it was a living bridge between generations. Veterans of the Revolution wept as they grasped his hand, while young Americans saw him as a link to the heroic age of their founding. In the words of one observer, “He was not of our soil, but he is of our soul.”

Final Years and Legacy

Lafayette spent his final years at his estate, La Grange, surrounded by his family and receiving correspondence from admirers around the world. He remained politically active, supporting liberal movements across Europe and advocating for constitutional reform during France’s July Revolution of 1830.

Though age had tempered his energy, his belief in liberty remained fierce. When asked late in life whether he regretted the risks he had taken, he replied, “If I had to begin anew, I would do the same.”

He died on May 20, 1834, at the age of seventy-six. At his funeral in Paris, thousands gathered to honor him as “the hero of two worlds.” His coffin was draped in both the French tricolor and the American flag, and he was buried in Picpus Cemetery beneath a layer of soil taken from Bunker Hill, the site of one of America’s earliest battles for freedom.

Nearly a century later, during World War I, American soldiers arriving in France visited his grave. Standing before it, Colonel Charles Stanton of the U.S. Army saluted and proclaimed, “Lafayette, we are here.” It was a tribute not just to a man, but to the enduring bond he forged between two nations and two revolutions.

Legacy

The Marquis de Lafayette remains one of history’s most remarkable figures: a nobleman who risked privilege for principle, a general who fought for liberty on two continents, and a visionary who believed that freedom and humanity transcended nationality.

In America, his name adorns towns, counties, universities, and parks—living monuments to a man whose courage helped secure independence. In France, he is remembered as the conscience of the Revolution, a symbol of moral integrity amid political chaos.

He stood with Washington, corresponded with Jefferson, defied kings, and survived tyrants. His belief that “humanity has won its cause” endures in every generation that sees liberty not as a gift but as a universal right.

Through his words, deeds, and example, Lafayette bridged the Old World and the New, leaving behind not just monuments but also ideals: equality, justice, and the conviction that freedom belongs to all.