Elizabeth Freeman: Claiming Freedom Through Law

Elizabeth Freeman—often remembered by the name Mum Bett—did not wait for freedom to be handed to her. She claimed it through the law. Born enslaved around 1744 in Claverack, New York, Freeman spent much of her early life under the control of the Ashley family in western Massachusetts. By the time of the American Revolution, she was living in Sheffield, listening closely as new ideas about liberty, rights, and equality entered public conversation.¹

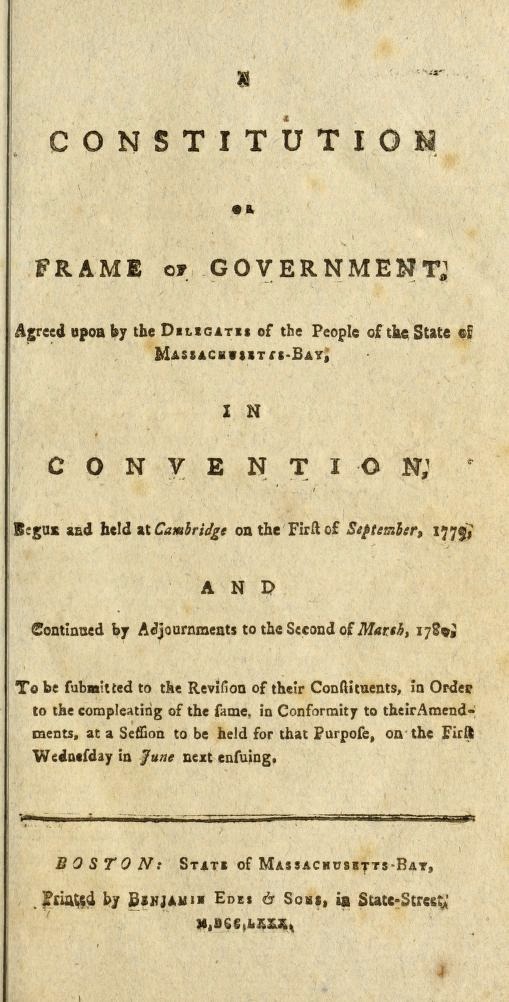

Those ideas would not remain abstract for Freeman. In 1780, Massachusetts adopted a new state constitution declaring that “all men are born free and equal.” Freeman took that statement seriously. With the assistance of attorney Theodore Sedgwick, she brought a lawsuit asserting that slavery itself violated the Constitution. Her case, Brom and Bett v. Ashley (1781), resulted in a decisive ruling: Elizabeth Freeman was legally free.²

Her victory did more than change her own life. It helped establish a legal precedent that effectively ended slavery in Massachusetts, demonstrating the power of civic institutions—and individual courage—during the nation’s founding era.

Listening to the Language of Liberty

Elizabeth Freeman could not read or write, but she was a keen observer of public life. She listened as white colonists protested British rule using the language of natural rights and equality. According to contemporaries, Freeman was especially struck by the Massachusetts Constitution’s declaration of universal freedom. She recognized the contradiction immediately: if liberty applied to all, it must apply to her as well.³

Rather than fleeing or rebelling, Freeman chose a path grounded in lawful civic action. She sought legal counsel and placed her case before the courts, trusting that the same legal system shaping the new republic could be used to challenge slavery itself. This choice reflected a sophisticated understanding of civic power at a moment when few enslaved people had access to legal remedies.

A Case That Changed Massachusetts

Brom and Bett v. Ashley was decided alongside another case, Commonwealth v. Jennison, which together dismantled slavery in Massachusetts without a single legislative act abolishing it outright. The court’s reasoning rested on the constitution’s language, signaling that written civic principles could carry real force when tested.⁴

Elizabeth Freeman’s case stands out not only because she won, but because she asserted her rights directly. She did not appear merely as evidence in someone else’s argument. She was a plaintiff, a legal actor, and a participant in the civic life of the Commonwealth. Her success reshaped how freedom was understood in Massachusetts and influenced broader antislavery efforts in the early republic.

Life After Emancipation

After gaining her freedom, Elizabeth Freeman chose to remain in Massachusetts. She worked as a paid domestic servant and midwife and later became a valued member of Theodore Sedgwick’s household, where she helped raise his children. Freeman negotiated her own wages and conditions—another assertion of independence and civic agency.⁵

She lived to see Massachusetts become the first state to end slavery through constitutional interpretation, a process she helped initiate. When Freeman died in 1829, she was buried in the Sedgwick family plot, a rare honor reflecting the respect she earned during her lifetime.

Civic Action Beyond the Ballot

Elizabeth Freeman never voted or held public office. Like many women and people of color in the founding era, she was excluded from formal political power. Yet her life illustrates a broader understanding of civic participation—one that includes legal action, moral reasoning, and the courage to insist that public principles apply universally.

Her case reminds us that the founding generation was not limited to lawmakers and soldiers. It also included individuals who tested the meaning of liberty in courtrooms, households, and communities. Freeman’s insistence that the law recognize her humanity helped define what freedom would mean in practice, not just in theory.

A Legacy of Lawful Resistance

Elizabeth Freeman’s story continues to resonate because it highlights the role of civic learning and engagement in shaping American history. She listened carefully, understood the power of words written into law, and acted decisively. Her legacy challenges modern readers to consider how civic knowledge—and the willingness to act on it—can expand rights and strengthen institutions.

As we reflect during Black History Month, Freeman’s life offers a reminder that civic progress has often depended on ordinary people who recognized injustice and used lawful means to confront it. Her courage helped move the nation closer to its stated ideals, one case at a time.

Explore more stories from the Revolutionary era in our Founding Generation series.

- National Women’s History Museum, Elizabeth Freeman (Mum Bett).

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-freeman - Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Historical Society, Quock Walker and the Abolition of Slavery.

https://www.mass.gov/guides/massachusetts-constitution-and-the-abolition-of-slavery - Library of Congress, Slavery in Colonial and Revolutionary Massachusetts.

https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/african/beginnings/ - Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, Article I.

https://malegislature.gov/Laws/Constitution - National Park Service, The Sedgwick Family and Elizabeth Freeman.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/self-emancipation.htm